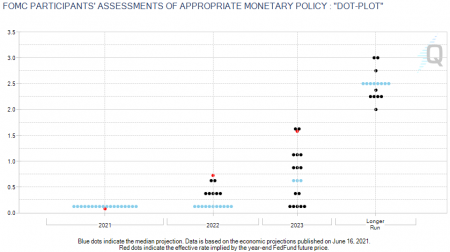

In our 2019 market insight titled ‘Federal Funds Rate projections. They expect what???’, we covered what the US Federal Reserve’s expectations for interest rate increases were. We felt at the time there was a mismatch between what the dot plot was indicating vs what the interest rate market was indicating. You can find the article here: https://www.framefunds.com.au/federal-funds-rate-projections-they-expect-what/

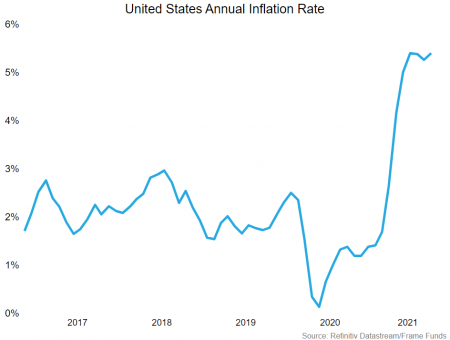

We are once again seeing a major dislocation between interest rate markets and central banks. It has stemmed from the unique combination of persistently high inflation data and policy makers who insist it is ‘transitory’. This piece will discuss how we got here, what is happening now and possible future changes in inflation and interest rates.

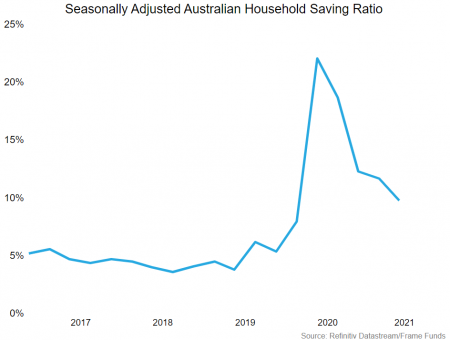

Household Savings

After the record amounts of monetary and fiscal support offered to economies in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, households were cash-rich coming out of lockdowns. This meant people were willing and able to spend when restrictions were eased, which resulted in a significant increase in demand for goods and services.

Global Supply Chains

The decrease in consumer demand that came with the shutdown of the global economy resulted in drastic cuts to production, leaving many ports and shipping services that operated at a severely diminished capacity. As the world emerged from lockdown, consumer demand came with it, meaning suppliers scrambled to adjust. Shortages of workers in key positions at ports and in transportation (truck drivers) meant demand outstripped supply and prices rose.

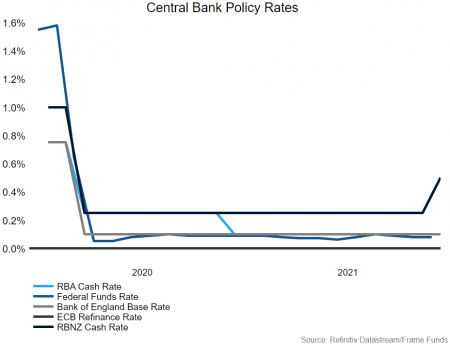

Global Interest Rates

Global Central Banks have taken the view that inflation is ‘transitory’. While this is probably the case, the big question is the timeline around the transition. Inflation can still be considered transitory and last two years, a scenario that would undoubtedly be very harmful to many low and middle-income earners. Hawkish notes have begun to creep into rhetoric from some Central Banks like the Bank of England and the United States Federal Reserve, with some going even further and increasing interest rates (Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Norges Bank and the Central Bank of Brazil). The Reserve Bank of Australia and the European Central Bank continue to take a softer policy stance. They are not looking to increase rates until 2024 and 2023 respectively.

While some Central Banks are more dovish than others, the general theme we have seen in the market is disbelief around the timeline of tapering. The US Federal Reserve maintains they won’t increase rates until tapering is finished, around July 2022. The market on the other hand (via the 30-day Fed Fund futures) is pricing in 48.9% chance of one increase by then, with an 18.7% chance of two increases to their interest rate target.

The RBA is even more dovish, with Governor Lowe reinforcing rate hikes will not be rushed into until inflation is sustainably within the 2-3 percent target range. The RBA projects underlying inflation will be no higher than 2.5 percent by the end of 2023, meaning an increase in rates before then is unlikely. Again, the market appears to not believe the RBA’s commentary, with the December ‘22 30-day Interbank Cash Rate futures contract implying an increase of almost 87 basis points at that time.

Who is correct?

There has been a decrease in yields around the world after the Bank of England bucked market expectations by not increasing rates at their November meeting, but there remains a significant mismatch between Central Bank rhetoric and market pricing.

There is sure to be significant volatility in interest rate markets in the short term as investors digest new data points and central bank commentary. Eventually, one or both parties will have to ‘catch up’ to each other as such a high disconnect cannot last forever. We believe the most likely outcome is the market and central banks will meet somewhere in the middle, with yields declining and central banks moderating towards sooner than planned rate hikes. This will be facilitated by economic data and inflation continuing to improve, with supply chain problems easing over the next 12 to 18 months.

One risk to this outcome would be supply chains remaining tight for longer than expected in combination with sustained high demand. This could cause a more permanent inflation risk. If inflationary expectations become permanent, we could see consumers beginning to ‘front run’ price rises by purchasing goods immediately instead of delaying buying. This scenario would require more aggressive action from central banks and could potentially be very destabilising for the economy.

*as at 11/11/21